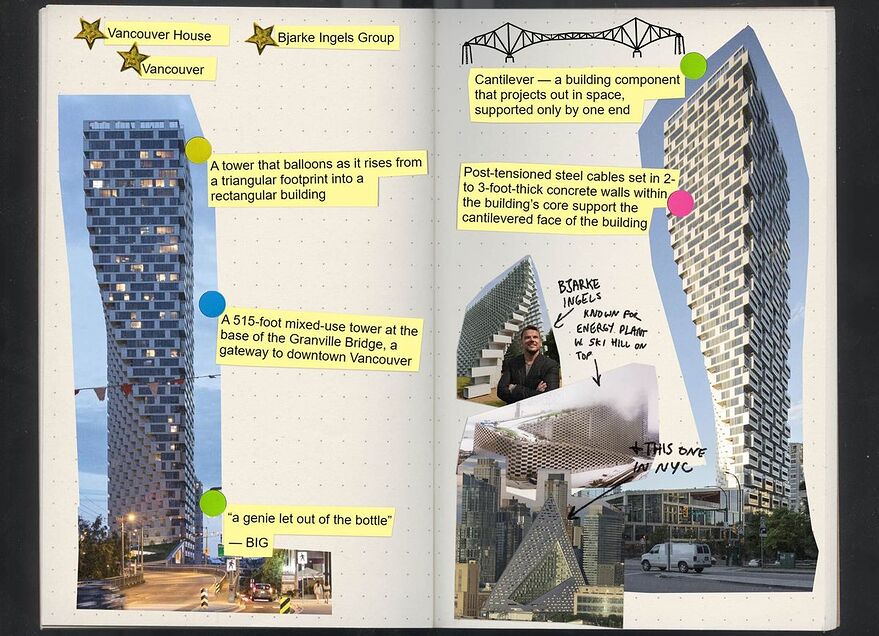

Vancouver Skyscraper Twists Around Zoning Restrictions

How do you build a tower like this in an earthquake-prone city? Very carefully.

Photos courtesy Bjarke Ingels Group. Illustration: Stephanie Davidson

Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group used limitations to its advantage with the gravity-defying Vancouver House apartment tower.

By

Amelia Pollard

January 7, 2023 at 9:00 AM EST

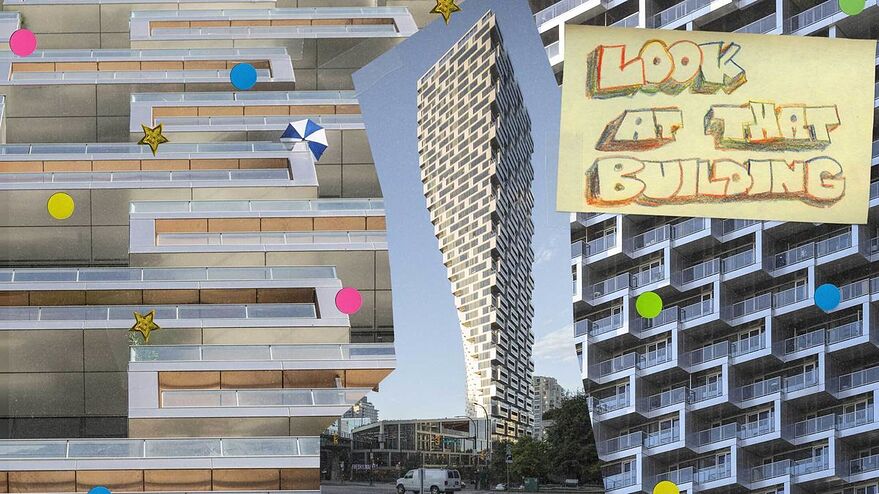

(This story is part of “Look at That Building,” a weekly Bloomberg CityLab series about everyday — and not-so-everyday — architecture. Read more from the series, and sign up to get the next story sent directly to your inbox.)

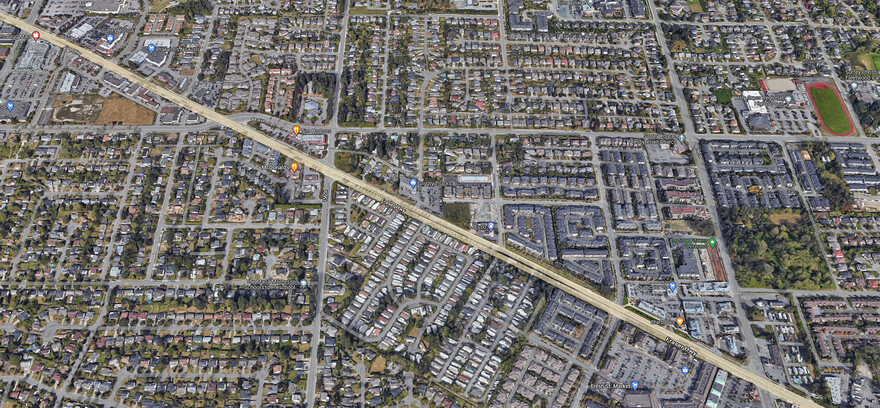

As drivers head from Vancouver’s suburbs to the city’s downtown, they’re now greeted by what looks like a gravity-defying building. The Vancouver House is a 490-foot high-rise teetering on a narrow base, twisting and expanding as it rises. The torquing tower serves as a new gateway to the city, appearing like a half-formed archway that frames the skyline and British Columbia’s North Shore Mountains beyond.

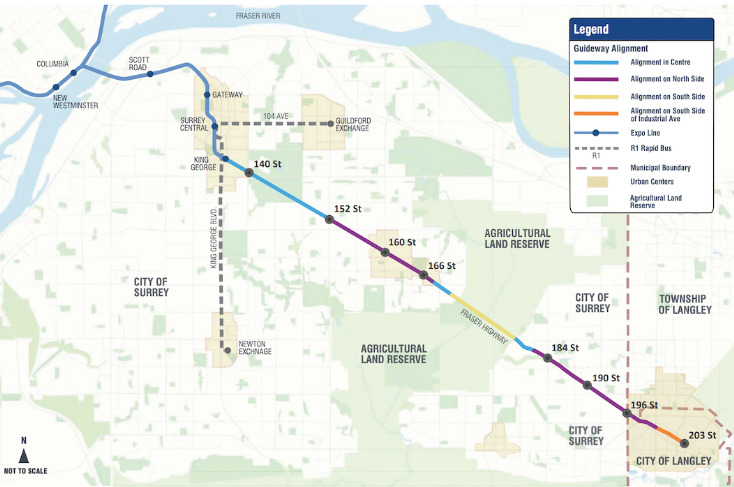

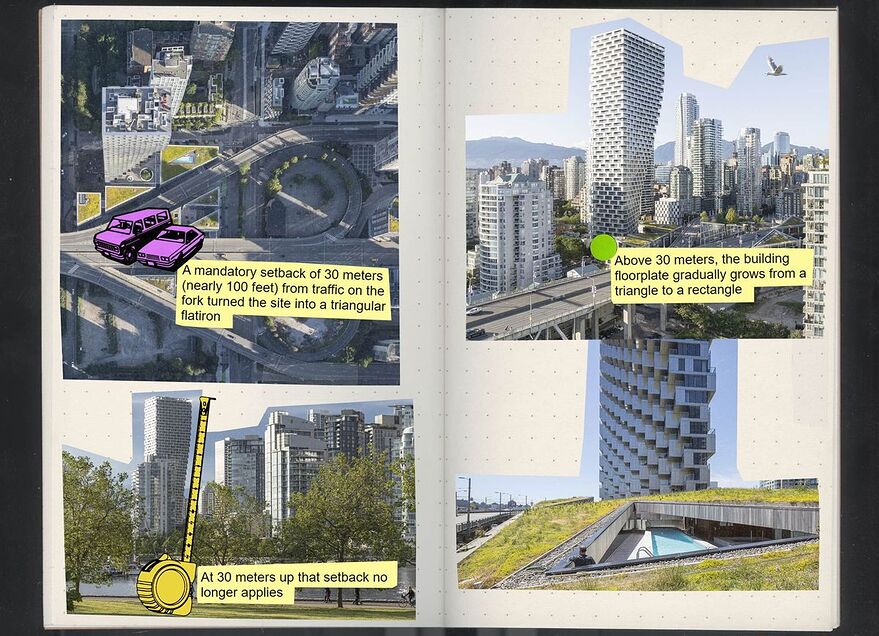

Designing the twisting apartment complex, which includes nearly 500 units, was no easy feat. The lot came with a laundry list of zoning restrictions: The high-rise couldn’t be too close to the street, it had to be at least 30 meters (nearly 100 feet) away from the Granville Bridge and it couldn’t cast shadows on a nearby park. Those constraints left just a small triangular footprint upon which architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group could erect a skyscraper.

Photos courtesy Bjarke Ingels Group. Illustration: Stephanie Davidson

But architects at BIG found a catch to the onerous restrictions: The building only had to be 30 meters from the bridge up until the skyscraper itself reached 30 meters in height, at which point it could widen and turn toward the Granville Bridge. As a result, the team designed the building to start with a triangular footprint which pivoted and expanded as it rose, so that as it nears its highest point, it transforms into a rectangular shape.

“The project is probably shaped more by constraints than by opportunities because of this very limited footprint that we had,” said Thomas Christoffersen, a partner at BIG and one of the principal architects on the Vancouver House, which was orchestrated by Vancouver-based real estate developer Westbank and completed in 2020. The process took a decade and involved nearly 100 of BIG’s employees.

Photos courtesy Bjarke Ingels Group. Illustration: Stephanie Davidson

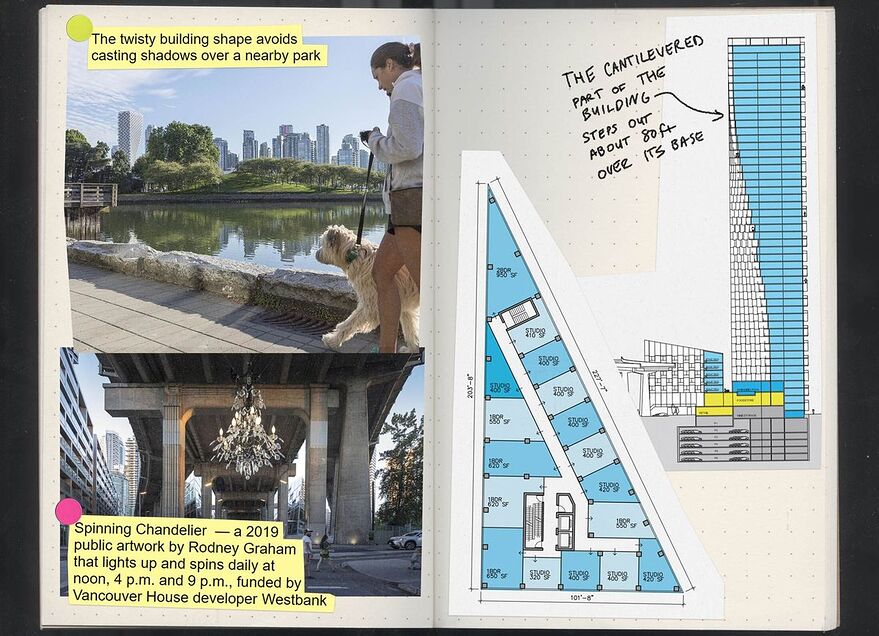

Because of its twisting design, structural engineering played a large role in the construction. BIG consulted with engineering firms Glotman Simpson and Buro Happold to ensure the tower — which steps out around 80 feet — was stable enough to meet stringent building codes in this seismically active city. (The architect declined to disclose how much the Vancouver House cost to build, while Westbank, the developer, didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

“It’s not only bigger on the top,” Christoffersen says. “It’s also asymmetrical.” To counter the heavier side of the building — and prevent it from leaning over — engineers strung cables through its walls to ensure “post-tensioning.” The post-tensioned steel cables, which are also known as tendons, are anchored to 2- to 3-foot-thick concrete walls of the structure’s core in order to keep the building steady.

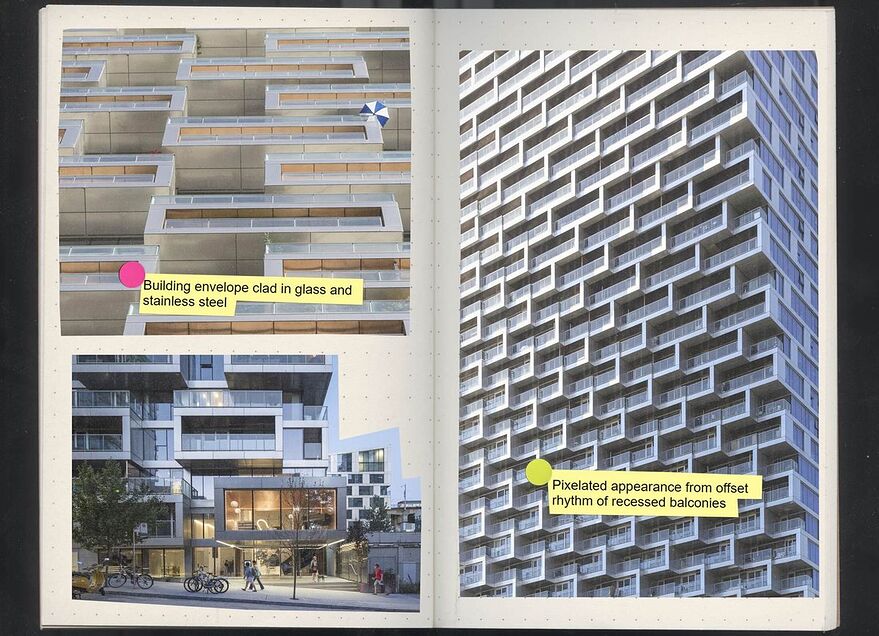

On top of that, the building’s facade needed flexibility so that it could move more than a typical building does. Although that didn’t have an impact on material used for the exterior, it meant that the firm had to be deliberate about how the exterior walls were put together, choosing larger joints and gaskets between panels to give them a bit more mobility, Christoffersen says.

Photos courtesy Bjarke Ingels Group. Illustration: Stephanie Davidson

So commonplace are shiny curtain-walled towers in Vancouver that it’s earned the nickname “City of Glass.” That holds true for the immediate vicinity around the Vancouver House, with the majority of nearby buildings either featuring glass or a matte finish. BIG wanted something different, a material that would reflect the light of its surroundings — especially the sky and sun, Christoffersen says. The architects opted for a glinting facade of stainless steel that frames the building’s recessed balconies. From some close-up angles, it resembles a gleaming beehive.

“The stainless steel really makes it stand out during certain times of the day,” he said. “It also has this changing appearance depending on the time of day and year.”

BIG and Westbank have teamed up on other striking designs that break Canada’s architectural status quo. The two also worked together on what Christoffersen calls a sibling building in Calgary, Alberta, known as the Telus Sky Tower. Like an inverted version of the Vancouver House, the Calgary building has a dramatic slope that narrows toward the top of the skyscraper. The partners are also working on two other buildings in Canada — one more in Vancouver and another in Toronto.

Photos courtesy Bjarke Ingels Group. Illustration: Stephanie Davidson.

Limiting the shadows that new construction can cast on parks and green spaces is a phenomenon that has sparked debates in other cities. In New York, the outcry over shadows reached a fever pitch around 2014 as a spate of new supertalls went up near Central Park, but has resurfaced in bouts over the years. For the Vancouver House, BIG had to be deliberate about which portion of the lot the skyscraper could stand on in order to ensure that a nearby park received sufficient sunlight throughout the day. The park prevented construction further south, and as a result, left a chunk of land nearby empty. Christoffersen says he likes the differing terrain: “It breaks up the scale of the lot, so it’s not all one development.”

But the residential tower isn’t the only construction BIG was responsible for on the site. The property also includes two adjacent, triangular lots that are sandwiched by the bridge and its off-ramps. The two buildings house a portion of University Canada West and ground-level retail. Lots that corner bridges are often unused — or at the very least, not creatively used — and BIG wanted to change that. Christoffersen says that the firm didn’t build beneath the underpasses, which don’t get much light, but instead built around them.

“We really tried to make something that feels more like a campus,” Christoffersen says. “We wanted to transform this sort of derelict piece of land under some bridges to something that is active and attractive.”

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-01-07/vancouver-delivers-a-gravity-defying-tower-with-a-twist