Texte complet : Montreal Hasn’t Quite Finished Pouring Money Into Long-Empty Olympic Stadium

Montreal Hasn’t Quite Finished Pouring Money Into Long-Empty Olympic Stadium

Built for the 1976 Summer Games, the “Big O” is both an architectural landmark and a budget-busting bête noire to Quebec taxpayers. Now it needs a costly renovation.

Olympic Stadium, with its inclined tower at right, has long been a Montreal landmark.

Photographer: Roberto Machado Noa/LightRocket

By Teresa Xie

March 22, 2024 at 8:00 a.m. EDT

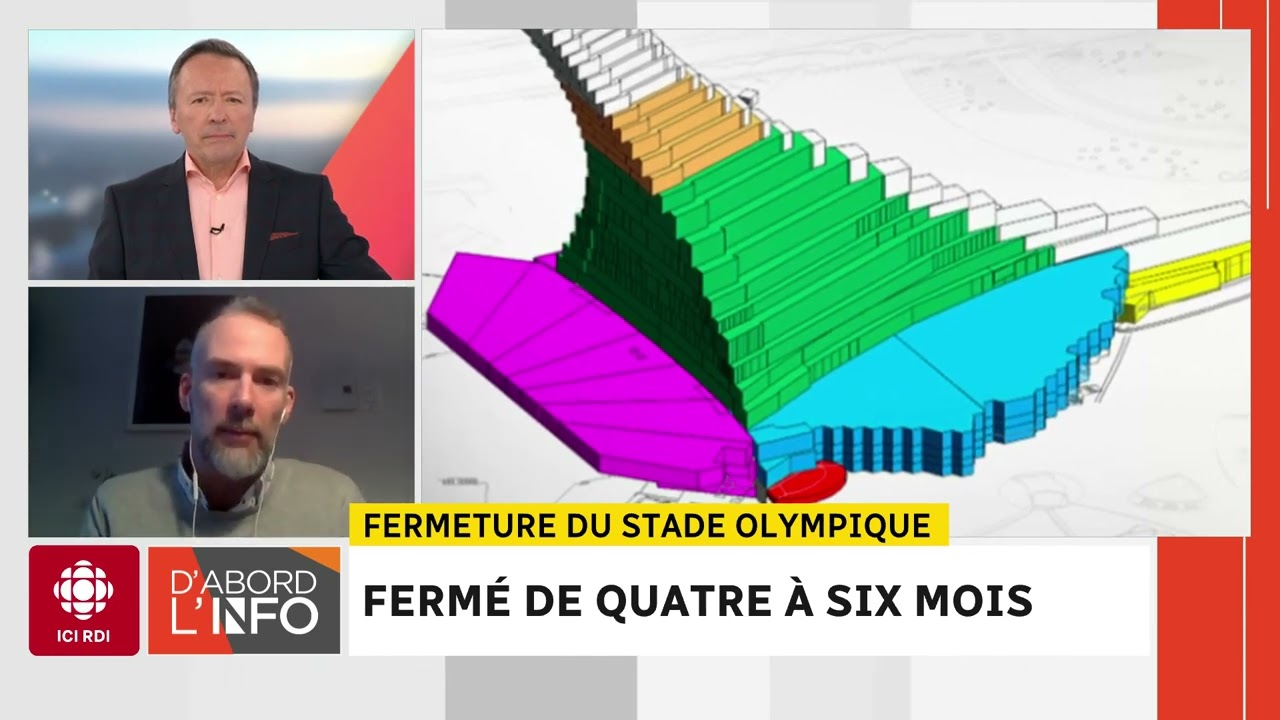

When Quebec’s government announced in February that it was planning to fix the roof of Montreal’s Olympic Stadium, it seemed, from an outsider’s point of view, an obvious plan. The stadium, built for the 1976 Summer Olympic Games, is an icon on the skyline of the Canadian city, and its decades-old fiberglass-and-Teflon roof is full of tears (about 20,000 to be exact). Quebec Tourism Minister Caroline Proulx told reporters in December that Taylor Swift would skip performing in Montreal during the Canadian leg of her Eras Tour this year because the stadium is in such poor shape.

But local residents know that just about anything that touches Le Stade olympique invites controversy. Infamous for the construction delays and budget overruns that saddled Quebec taxpayers with a billion-plus-dollar debt that took three decades to repay, the facility known to Anglo-Montrealers as “the Big O” (or “the Big Owe”) is still racking up costs: The price tag on the proposed replacement roof is C$870 million (US$642 million), and the project will take four years to complete.

“It would probably be the first time we spend such an amount of money for a roof in a stadium that is currently empty,” said Nicolas Gagnon, Quebec director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation.

To be fair, the multi-purpose facility, which can seat up to 60,000, isn’t literally empty: In recent years it has hosted professional soccer games, as well as concerts and exhibitions. During the Covid-19 crisis, it served as a mass vaccination site. But the venue hasn’t had a regular tenant since since the Montreal Expos baseball team left the city in 2004. In 2012, the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League stopped using the stadium for their playoff games.

Booking the facility during the winter is a gamble: Events cannot be held in the venue if there are more than three centimeters (1.2 inches) of snow.

Typically, 1970s-vintage multipurpose stadiums don’t enjoy long lives after their sports teams move away, but Olympic Stadium has survived, in part because it would too expensive to demolish. Thanks to the complexity of its construction and location atop a Metro station, the province estimated that cost at up to C$2 billion.

An aerial photo of the Montreal Olympic Stadium complex in 2019.Photo by Sebastien St-Jean / AFP via Getty Images

It’s a figure that Gagnon and his organization have questioned. “It doesn’t make sense when compared to the costs of dismantlement for similar structures in North America,” he said. In New York City, for example, tearing down the original Yankee Stadium in 2010 only cost around $25 million.

Designed by French architect Roger Taillibert, the donut-shaped structure is part of a complex of similarly swoopy Olympic venues, including a recently renovated inclined tower (the world’s tallest) and a velodrome-turned-natural-science museum. The assemblage makes a striking keepsake of the ’76 Olympics, and it has some passionate defenders among local preservationists and modernist architecture enthusiasts. But others see it a money-sucking pit.

“There was always this uneasy feeling of, is it a landmark, or is it a curse?” said Dinu Bumbaru, policy director at Héritage Montréal, a nonprofit organization that works to protect and promote the city’s historic buildings and culture. That includes the Big O, which the group believes is an important architectural and engineering landmark that’s worth preserving. Most local leaders agree that it would be politically delicate to destroy Olympic Stadium, which remains a powerful, if little used, civic symbol.

The stadium’s groundbreaking design was to feature an umbrella-like retractable roof, opened via cables suspended from the adjoining leaning tower. But the structure wasn’t finished in time for the Olympics it was built to host. When the roof mechanism was finally installed more than a decade later, it proved troublesome and was eventually abandoned.

Major League Baseball’s Montreal Expos enjoy some fresh air at Olympic Stadium in the mid-1980s, with the stadium’s fabric roof retracted at the top of the adjoining tower. The Expos left Montreal in 2004 and became the Washington Nationals.Photographer: Focus On Sport/Getty Images North America

“They tried to sort of push the limits of the technologies that they had at the time,” said Daniele Malomo, a civil engineering professor at Montreal’s McGill University. “It was a project that was so explorative, and not well thought-out.”

Malomo said that although he can’t speak to how much Olympic Stadium’s removal would cost, the unusual engineering and materials involved in its construction make it difficult to demolish. The curved ribs that hold the stadium up are made of prestressed concrete reinforced with steel cables that are under enormous tension. “Demolishing the Stadium using explosives or standard techniques is not going to be possible,” he said. “When you cut prestressed concrete, the energy will be released instantaneously.”

Additionally, the environmental impact would be considerable, according to Malomo. “There’s a huge amount of concrete that would just become garbage that is difficult to reuse,” he said.

Montrealer Olivier Desrochers, who lived near the stadium in the late 1990s, is among those who hope that it still has a future. Now a resident of the nearby suburb of Laval, he has fond memories of rollerblading in the park around the facility and being in awe of seeing the structure every time he exited the Metro. “That whole area is just something else,” Desrochers said. “You can just kind of escape in a world inside a world.”

Desrochers said that while he understands the hesitation behind using the facility primarily for sporting events or concerts, there are other ways to invest in the space, such as using it for educational purposes. “Repurposing the stadium could bring new life, new ideas and new opportunities for the city,” Desrochers said.

The recently renovated stadium tower has a 45-degree lean and an observatory at the summit.Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images

The Quebec government, which signed a C$729 million contract with Groupe Construction Pomerleau-Canam to rebuild the stadium roof in March, has said the investment will be worth it. Over 10 years, the renovated stadium could generate up to C$1.5 billion through tourism and more frequent events. (While it won’t retract, the new roof will feature a transparent base to allow natural light in, and it should last for 50 years.) Beyond potential economic benefits, a 2017 study commissioned by Quebec’s Régie des installations olympiques concluded that the Olympic Park, which is home to the stadium, is a site of heritage value.

But many locals object to pouring more public money into the facility, suggesting those funds are more urgently needed elswhere. There’s a housing crisis in Canada, as vacancy rates for rental apartments fell to an all-time low of 1.5% by October of last year and rent increases climbed to a record high. But Bumbaru of Héritage Montréal argues that they are two separate, but important issues. “Even if you don’t spend the money on the stadium, the housing issue will not be solved,” Bumbaru said. “It requires much more money.”

For those surrounding the stadium on the city’s east side, it can be hard to imagine a Montreal without the Big O. The Olympic complex is a longtime anchor of the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve district — a historically Francophone and working-class neighborhood. Alexandre Lotte, 26, has lived next to Olympic Stadium all his life. He goes to a gym inside the facility, can see its tower from his window, and still believes it brings value to the city.

“I know the roof is expensive and that there is a crisis,” Lotte said. “But at the same time, it would be such a shame if we had to demolish the stadium and think that as a society, we can’t even take care of it.”

![]()