Texte intégral

Free Parking Is Killing Cities

With the pandemic opening up streets, Donald Shoup and his followers say it’s time to stop subsidizing drivers at the expense of everyone else.

Illustration: Joel Plosz for Bloomberg Businessweek

By

August 31, 2021, 7:00 a.m. EDT

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Share

Tweet

Post

Email

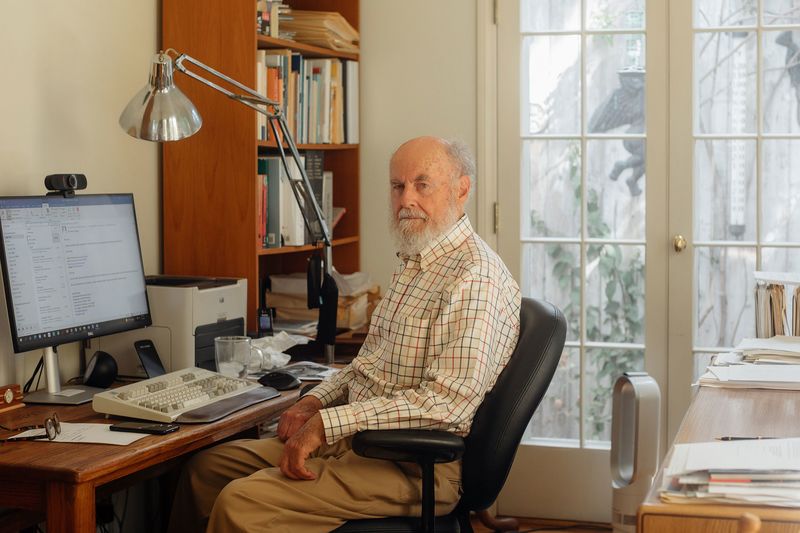

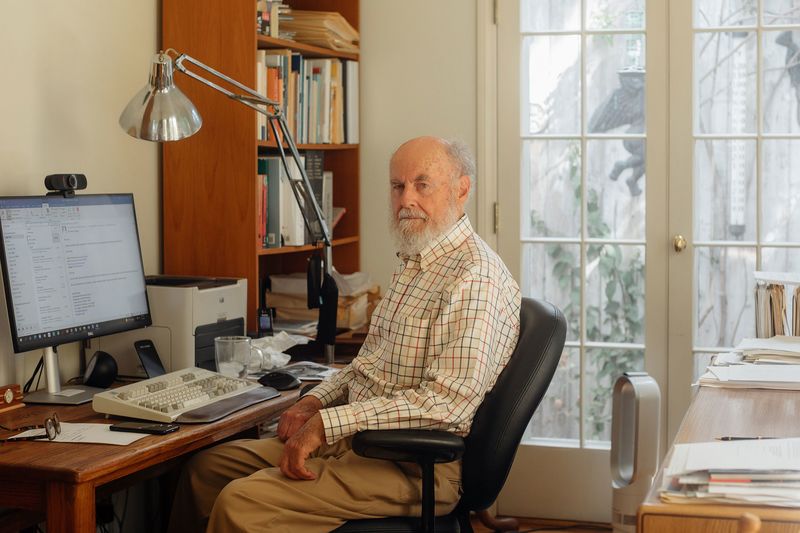

Over a Zoom call from sunny Los Angeles, Donald Shoup—sporting a big white beard, a brown cardigan sweater, and a marketer’s telephone headset—was yelling at me. “Oh, how terrible, you have to move your car, so they can sweep the road. I think that’s just awful,” he said, with audible italics. “To overcome the base desires of people like you”—people like me?—“you have to give the money back to the neighborhood.”

I’d made the mistake of griping to the bona fide king of parking reform that owning a car in New York City was annoying. Twice-weekly street sweeping forces a large group of people to fight for a small number of free curbside spots that they must then vacate frequently. It’s the rare game of musical chairs that requires insurance. And for most people, exorbitantly priced garages aren’t really an option. The free spaces are the only way to make owning a car in New York feel sustainable.

Shoup at his desk.

Photographer: Bethany Mollenkof for Bloomberg Businessweek

Shoup wasn’t having it. “People have to ask—do they want free Wi-Fi, or do they want free curb parking for her?”

He didn’t say as much, but by his definition, I was a person suffering from paid parking derangement syndrome. In his writing he describes this condition as “the acute onset of extreme paranoia in reaction to the prospect of paying for parking, leading the afflicted to speak in hyperbolic language and to lose touch with reality.” Guilty as charged.

This wry octogenarian is a distinguished research professor in the department of urban planning at the University of California at Los Angeles. He wrote a 765-page book on this subject, The High Cost of Free Parking, which came out in 2005 and outlines his case against America’s decision to hand over an astonishing amount of free land to cars. Among urban planners, academics, economists, civil servants, and even some regular old city dwellers, the book stands as the most salient argument for renegotiating our toxic relationships with our vehicles. Shoup pitches parking as the most obvious, least-discussed way to make progress on a host of issues too often dismissed as intractable, including affordable housing, global warming, gender equity, and systemic racism. “All parking is political,” he writes in the book, especially because we refuse to pay for it. He says he debated calling the treatise Aparkalypse Now.

America’s 250 million cars have an estimated 2 billion parking spots and spend 95% of their time parked. To make cities more equitable, affordable, and environmentally conscious, Shoup makes the case for three simple reforms:

-

Stop requiring off-street parking for new developments.

-

Price street parking according to market value, based on the desirability of the space, the time of day, and the number of open spots.

-

Spend that revenue on initiatives to better the surrounding neighborhoods.

If people had to pay for street parking, he argues, it would bring in money to pay for local repairs, infrastructure (like that free Wi-Fi he was talking about), and beautification. It would also make public transit more attractive and force many curbside cruisers to head straight for parking garages and other paid spots—a win for neighborhood air quality, global greenhouse gas levels, and those still playing those two-ton games of musical chairs.

As anyone who lives in a city knows, the pandemic blew up most of what we understood about parking in America. Oh, it was possible this whole time to hand over parking spaces to restaurants? To turn whole streets into semi-permanent pedestrian thoroughfares? To cut traffic enough to yield noticeable improvements in air quality? All it took was a once-in-a-century public-health catastrophe.

I asked Shoup if he saw all this coming. No, he said. For a long time, there was just nobody else talking about it. “The first article I wrote that had the word ‘parking’ in it was in 1970,” he told me. These days he’s the most frequently referenced figure in all contemporary conversations on civic parking reform, one whose ideas are only now starting to be put into practice in a handful of cities around the country.

For 50 years, Shoup has been trying to get people to admit that there’s no such thing as free parking. If the subject is finally up for debate, are the sufferers of paid parking derangement syndrome ready to listen?

Shoup

Photographer: Bethany Mollenkof for Bloomberg Businessweek

“Nobody wants to grow up to go into parking,” Shoup says. He grew up in Long Beach, Calif., assuming he’d go into economics, which he kind of did. He chose land economics for his doctoral dissertation, so he sort of backed himself into it. According to his research, U.S. cities dedicate more land to parking than any other single use, including housing and commercial space. No academics had paid much attention to why or whether that was the right call. In 1968, with his Yale Ph.D. in hand, Shoup decided to keep looking. “It seemed kooky,” he says, but important and undercovered. Such subjects require stubbornness, he says: “Often you have to stick to it for a while, even if it’s discouraging.”

In that department, arguing against parking subsidies definitely qualifies. In many cities decades-old ordinances require real estate developers to set aside a certain amount of space for parking—usually, a shocking amount. America has an average of 1,000 square feet of parking for each car, vs. 800 square feet of housing per person. Shoup attributes this upside-down status quo to city planning that amounted to back-of-the-envelope math. “People used to think that parking requirements were equivalent to natural numbers, like the boiling point of water or the speed of light,” he says. “They were guesses.”

Shoup met few government officials, real estate developers, or city dwellers eager to make parking tougher and pricier. His ideas didn’t start to gain something resembling traction until the late 1990s, when he’d begun teaching at UCLA and working on his book in earnest. As he brought on a series of grad students as editors, many of those who saw economics as a way to solve other city problems began to share his view that charging for parking would help. One of those editors, Douglas Kolozsvari, met Shoup 20 years ago, when he went to pick up an application for UCLA’s urban planning department and saw the professor sitting at the secretarial desk. “He asked what I was interested in,” recalls Kolozsvari, whose answer was air quality. Along with the application, Shoup handed the young man a chapter of his manuscript and told him to read it.

Kolozsvari says Shoup encouraged brutal feedback. “He wanted people to be as critical as they could be so he could make the book better,” he says. “He also liked his jokes in there.” Some of his peers were put off by Shoup’s style and zealotry, but the professor’s fans often became superfans, then acolytes who took his ideas to urban centers across the U.S. and elsewhere. Some appreciated his no-BS affect; others, that his research specialty didn’t have much competition. “Making your name studying traffic congestion is tough because so much has been done at it, but parking is just wide open,” says Michael Manville, another former Shoup grad student. Caveat: There are downsides to the field’s low profile, he says. “It’s not that I wrote an article about parking and now I’m the Rock.”

It’s the rare urban planning expert with a fan base in the thousands, but Shoup is one of them. There are more than 5,000 members in a Facebook group called the Shoupistas: UCLA alums, academics, consultants, and public officials from around the world who praise the professor as, variously, a legend, passionate, hilarious, and even easygoing.

Perhaps surprisingly, Shoup and most Shoupistas I spoke with say they own cars and only oppose underpriced parking. (“I don’t like paying for parking as much as the next person,” says Kevin Holliday, who created the Facebook group in 2008. “I don’t like paying for gas, either.”) We aren’t going to eliminate cars any time soon, they say, so we need to make parking beneficial to the communities around the spaces. And though there’s a big difference between having fans with urban planning degrees and fans who can sign bills into law, the work Shoup started a half-century ago is starting to change policy, too.

So far, Shoup’s ideas have found purchase mainly in liberal enclaves. To put his reforms into practice, officials need to start from the position that cars are a necessary evil, says Leah Bojo, a Shoupista who works as a land use consultant in Austin and has focused on green initiatives. “It’s not great to have lots of cars in cities, contributing to air pollution and circling around looking for a spot,” she says. “There are certain instances when they are the best choice, and that’s all fine.”

In 2011, Bojo helped set up the first of Austin’s Parking Benefit Districts. The city put meters on formerly free spaces in an area near the University of Texas’ west campus—where there was an influx of students and not enough housing—with the proceeds earmarked to fund bike lanes, pedestrian lanes, and other improvements. Neighborhood residents got to pick some of the projects, and the rest of the revenue went to similar efforts in other parts of the city, she says. The reviews are positive, and today Austin has four such districts. Revenue from parking meters recently approved near a popular lakeside running trail will go partly to fund trail landscaping and repairs.

Most American restaurants have at least three times the square footage devoted to parking as they do to the restaurant itself. During the pandemic, Austin, like many cities, passed legislation permitting restaurateurs to turn lots and curbs into extra dining space. “There were all these restaurants that people wanted to keep around,” Bojo says. “It hasn’t been the crisis that people thought it would be.” Covid germs notwithstanding, most days, Austin’s air quality is markedly better than it was before the pandemic, she notes.

“They’ll say, ‘Well, gee, these curbside cafes are pretty great.’ It was unthinkable before”

In Berkeley, Calif., city councilmember and Shoupista Lori Droste has looked to parking as a way to subsidize housing affordability. This is, in some ways, a corrective. In a research paper from a few years ago, Shoup estimated that construction costs for parking structures in a dozen U.S. cities averaged $24,000 per space aboveground and $34,000 per space underneath—or roughly two to three times the net worth of the average Black or Hispanic family at the time. These costs tend to get passed along to renters. “As council members, we write a lot of policies, but the one area that we can have the biggest impact in people’s day-to-day lives is in land use,” Droste says.

In 2014, when she was elected, Berkeley required one off-street parking spot for every unit of housing and was considering adding even more spots to a downtown area where they were already plentiful. Droste saw that proposition as an unneeded giveaway likely to jack up housing costs. “For the first however many years I was a councilperson, I was intolerable at any sort of cocktail party because I would just talk to people about parking,” she says. “I knew that the only way I’d be able to get some movement on this is if I have a really ridiculous-sounding proposal to pass, so I called it the Green Affordable Housing Package. How could you vote against that?”

During a Berkeley City Council meeting earlier this year, officials said that 60% of the city’s greenhouse gases come from transportation, and Berkeley has grown by 10,000 people in 10 years. Not requiring developers to spend tens of thousands of dollars on a parking spot would free up funds to build more affordable housing and incentivize more public transportation use. Droste’s bill aimed to lower housing costs and emissions, principally by repealing Berkeley’s requirement that each home have a dedicated parking space. “Do we want housing for cars or housing for people?” was her mantra. Even in Berkeley, the bill sat in planning commission purgatory from 2015 until earlier this year, when it was brought up for a vote and passed unanimously.

It’s not an especially sexy measure by most people’s standards, but to the Shoupistas, ending residential parking requirements is a big deal. Now, Droste says, Berkeley developers will have to ask for approval to add more parking, which she says will probably mitigate rising costs.

Cars being moved for alternate side parking on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, 2020.

Photographer: Brittainy Newman/The New York Times/Redux

Droste stresses that Berkeley parking hasn’t suddenly become a pain like New York’s. For one thing, many of today’s driving-age Berkeleyites, including Mayor Jesse Arreguín, don’t have licenses and don’t seem interested in getting them. For another, the Berkeley City Council is mindful of concerns about knock-on effects from her law. The city still has plenty of parking, Droste says, and she’ll keep an eye on the supply. “Nobody is saying if you choose to drive, you should be circling around the block.”

Droste and Bojo are among the handful of Shoupistas who’ve managed to translate the professor’s ideas into policy. They’re betting that more civic leaders will soon join them. “I’m sort of a parking and zoning evangelist,” Droste says. “Because parking really does touch everything.”

Some other parking reform efforts are trying to take cars more fully out of the equation. In car-heavy Phoenix, real estate developers are building a 17-acre neighborhood called Culdesac Tempe that won’t have any parking, period. (Residents and visitors will have to bike or take public transit.) Many time zones east, in Paris, Mayor Anne Hidalgo said last year that she intends to remove roughly half of the city’s 140,000 parking spaces in favor of wider sidewalks and bike lanes and more room for car-sharing and bike lots. Hidalgo has said her aim is to make the city feel more like a group of neighborhoods in which people can walk to any of their major needs within 15 minutes.

In U.S. cities where parking spots have become open-air restaurants or, in many cases, enclosed wooden longhouses, things don’t feel so settled. All the more reason, the Shoupistas say, for more permanent decisions.

As people return to work, start traveling again, and begin relying on their cars to run errands, meet friends, or go out to eat, it seems inevitable that they’ll, you know, want those parking spots back. Shoup, whose undergrad degree was in electrical engineering, says he’s confident there will be a long-term hysteresis effect. “If you have a magnet and you expose it to the coil of electricity, it changes the magnetism—it makes it go back and forth,” he says, explaining the concept slowly. “The electrical current has changed the magnetism, so when you remove the current, it doesn’t go back to what it had been. It doesn’t snap back like a rubber band.” He pauses to see if I understand. “It has changed forever.”

Shoup says he hopes this theory will hold true even in places where finding free parking is a competitive sport. “In the densest areas like Manhattan or Brooklyn, they’ll see that curb parking is not the highest-value use of the land,” he says. “They’ll say, ‘Well, gee, these curbside cafes are pretty great.’ It was unthinkable before.” Immediate local benefits are the key, he says. In a place such as New York, the hiking of parking rates based on demand and peak hours should be a winning issue if the money goes to fund cleaner streets, bigger sidewalks, and other perks.

Skeptics can be forgiven an eye roll. New York is a great example of a city where residents tend to distrust, with good reason, that added levies will actually find their way to the promised public works projects. (Its subways, for example, have grown steadily less reliable over a decade of reckless underinvestment by ex-Governor Andrew Cuomo.) And in any city there are some commuters who don’t care about sidewalk cafes, or people for whom paying surge pricing in busy central areas will represent a real financial hardship. To that, the Shoupistas can say only that if you own a car, you can afford to park it. Otherwise, someone else is paying the price.

Shoup says he has faith that the moral arc of the universe bends toward less parking. He doesn’t expect to live to see all his reformist dreams fulfilled, but, he says, the Shoupistas will. Together, they’ve already surpassed the low bar set for the relative few in his chosen field. “The subjects that we study in academia are hierarchical,” he says. “National affairs and international affairs seem really important, then the state government is a step down. Local government? That’s parochial. And what is the lowest class that you could study in local government? That would be parking.” Besides the potential community value, he was drawn to parking research all those decades ago because there seemed to be so much to learn. “I’ve been a bottom feeder for all these years,” he says. “But there’s a lot of food down there.”