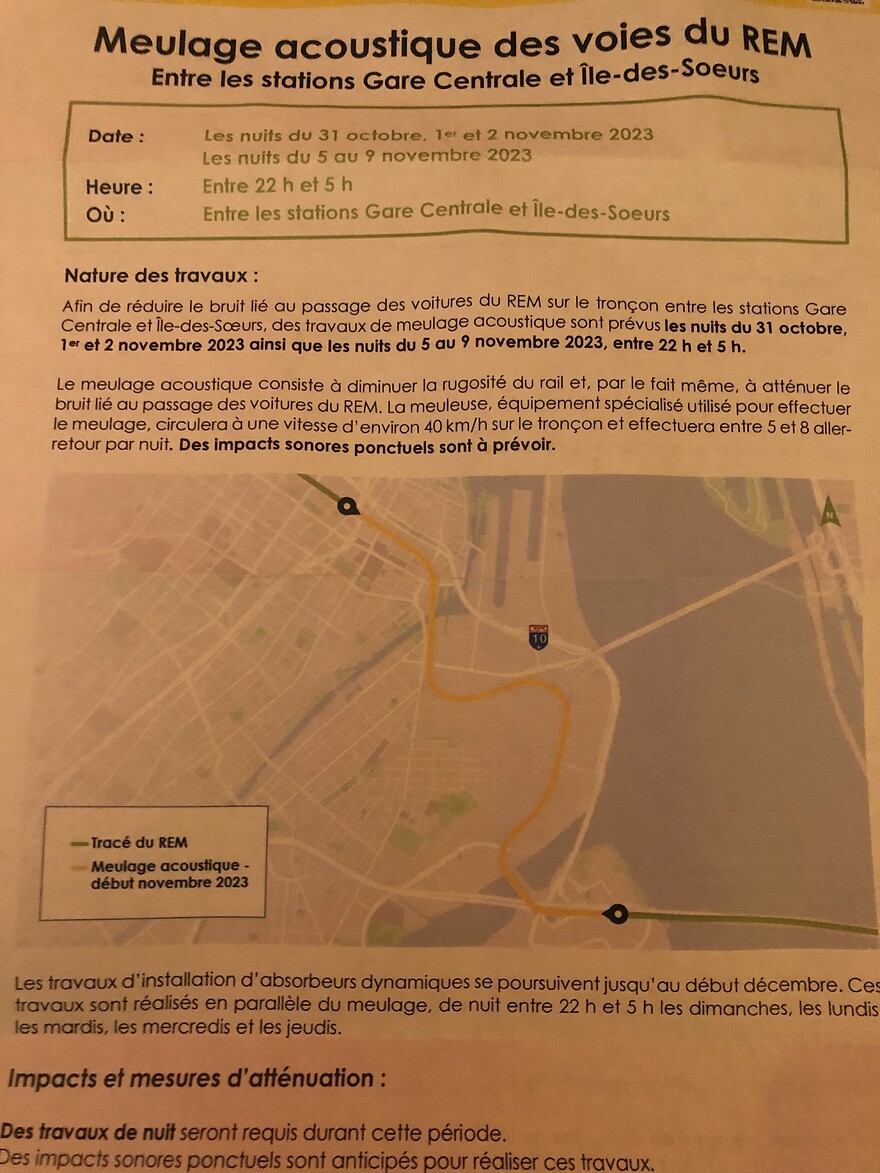

Article de Bloomberg/CityLab sur le REM

How Montreal Built a Blueprint for Bargain Rapid Transit

At $139 million per mile, the REM is far less costly than similar recent projects. Cities with ballooning transit budgets can learn from its approach.

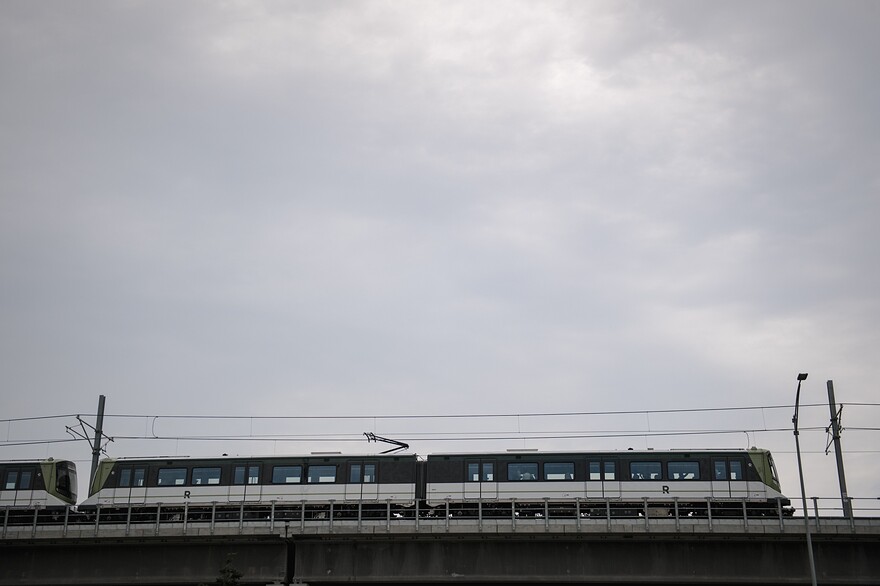

Visitors ride the Reseau Express Metropolitain (REM) light rail during its inauguration ceremony in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, on Friday, July 28, 2023.

Photographer: Andrej Ivanov/Bloomberg

By Jonathan English

October 30, 2023 at 9:00 a.m. EDT

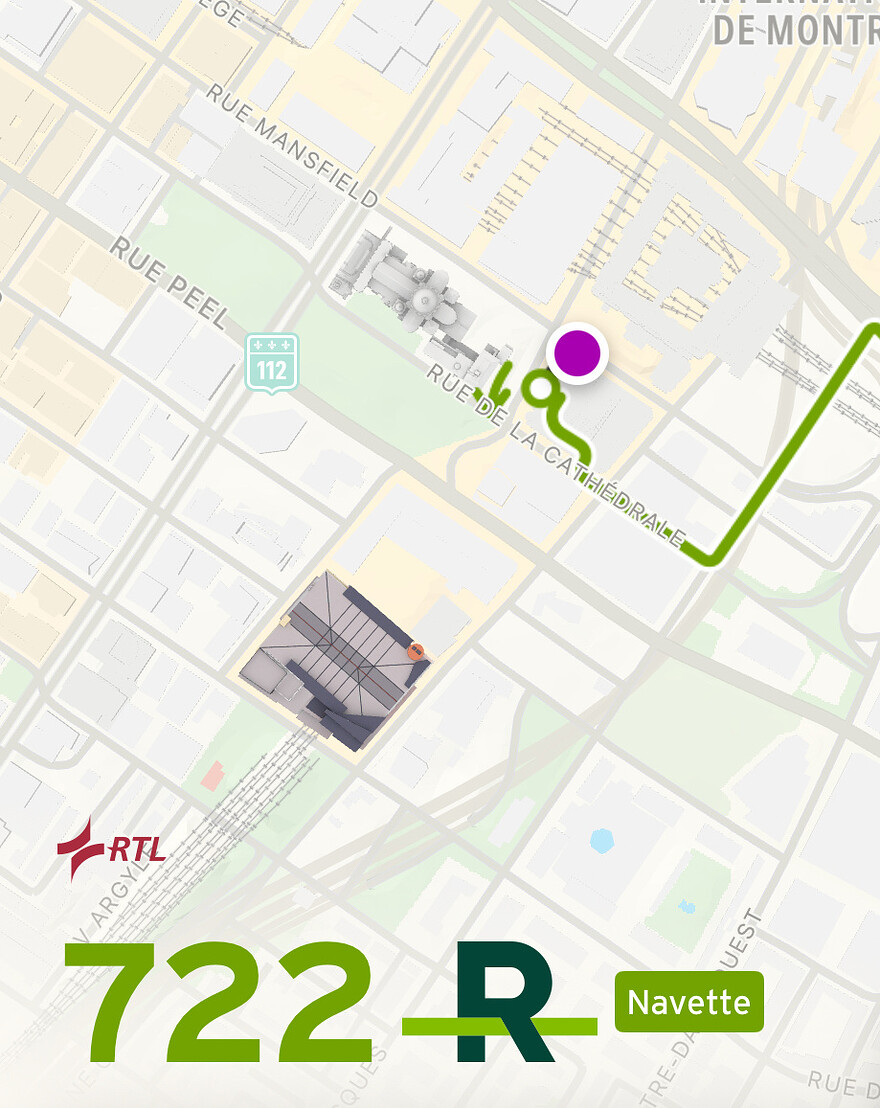

This summer, Montreal opened the first phase of its new rapid transit system, the Réseau express métropolitain (REM). Riders can now catch sweeping views of the city on the fully automated train, which runs elevated from downtown to the suburbs south of the St. Lawrence River. Though this first phase is only a small part of the overall network under construction, the REM is already serving 30,000 riders every day.

But the REM is more than a useful new transit line for Quebec’s largest city. It is in many ways unprecedented among recent North American transit projects, and bears valuable lessons for other cities.

First, at 42 miles in total, the REM is far larger than the subway extensions that many cities have seen in recent years. The 1.8-mile Second Avenue Subway in New York, or the 9-mile D Line extension in Los Angeles, are tiny by comparison. Second, the REM is financed and delivered by an arm of Quebec’s public pension fund manager, known as CDPQ Infra. This approach — in contrast to the traditional model of government financing and delivery by a public transit agency — has received considerable attention from cash-strapped governments struggling to fund expensive infrastructure projects.

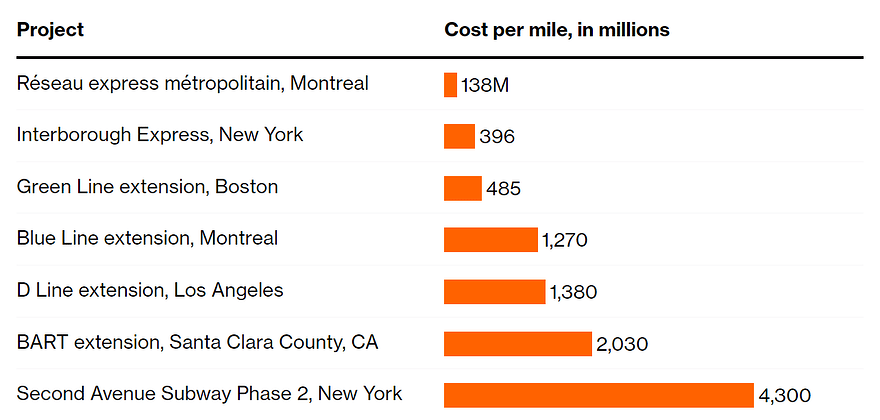

But by far the most important reason to pay attention to the REM is its cost. Even after the just-announced increase to C$7.95 billion ($5.82 billion) its price tag is a mere C$119 million per kilometer, or $139 million per mile. According to data from the Transit Costs Project at New York University’s Marron Institute, the costs of other North American transit projects are literally multiples of that.

On a per-mile basis, the latest phase of LA’s D Line extension is $1.38 billion, while the planned second phase of the Second Avenue Subway will be a whopping $4.3 billion. In the San Francisco Bay Area, a BART extension to Silicon Valley has faced controversy for its cost of $2.03 billion per mile, and is expected to serve fewer than half as many riders as are served today by the REM’s first phase alone. The REM is just as much an outlier in Canada: The Blue Line extension being built a few miles away by Montreal’s transit agency is strikingly more expensive at $1.26 billion per mile, even taking into account that it’s all underground.

It’s worth noting that the REM is not a straightforward project. It included the complete rebuilding of a century-old tunnel, long elevated segments, and two complex interchange subway stations — one of which is the second-deepest station in North America. In contrast, the much simpler Green Line extension in Boston — which was built above ground in an existing rail corridor — cost $485 million per mile. Judging by the REM’s peers, you’d expect an exorbitant figure.

Compared to Other Recent Transit Projects, Montreal’s REM Is a Steal

Source: Transit Costs Project at New York University’s Marron Institute

A few factors help explain why the REM is instead such a bargain. One advantage is that CDPQ Infra was able to take advantage of existing rights of way to create the route, rather than needing to dig costly tunnels or demolish buildings. In one area, they repurposed an old rail tunnel. Another section uses a transit corridor that was created, in an act of impressive foresight, as part of the recently built Samuel De Champlain Bridge. Some of the REM also runs along an expressway. That might not be the most pleasant place to board a train. But because the new system connects to a high-quality bus network, with terminals that provide shelter from the elements and allow the buses to pull right into the station, it’s still easy enough for riders to access less than ideally located stations. This enables CDPQ Infra to build along these cheaper corridors while still attracting considerable ridership.

Another factor in the cost savings relates to the speed of delivery. The seven years from its announcement in 2016 to the first phase’s completion in 2023 is fast, considering most transit projects go through years of public debate, often followed by lawsuits, before construction even begins — with costs mounting the whole time. It helped that CDPQ Infra designed, financed, built and now operates the system on its own, shepherding the project as a single entity from beginning to end, according to Philippe Batani, the organization’s executive vice president. That let it avoid the delays that come with negotiations between multiple actors over issues like contracts and interagency coordination.

Strong political backing from all levels of government was also critical. The premier of Quebec and mayor of Montreal made the project a top priority and collaborated closely on it. This helped CDPQ Infra overcome obstacles that frequently bog down other projects, including NIMBY objections and conflicts with other agencies and utilities. In fact, Quebec passed a law that requires municipalities to respond in a timely manner to CDPQ Infra’s requests for permits and other forms of cooperation.

This political support brought down costs in another way: It smoothed CDPQ Infra’s path toward building most of the REM as an elevated system, which is much cheaper than underground construction. Even though many riders prefer looking out at city views rather than being in a dark tunnel, elevated rail is often not even considered by agencies for fear of provoking NIMBY backlash against the noise and visual impacts of overhead trains. But the REM’s strong political support largely shielded it from such complaints. (That political support wasn’t sustained after a change in elected leadership: An extension project known as REM de l’Est, proposed in 2020, was quickly abandoned after significant neighbor opposition.)

A REM train arrives at the station in Ile-Des-Soeurs in July. While construction of the elevated line attracted complaints from nearby residents, political support allowed the project to continue.Photographer: Andrej Ivanov/Bloomberg

So what lessons can be drawn from all of this? Perhaps most important is that strong political and institutional backing enables transit projects to overcome inevitable obstacles. If it takes weeks to get a decision on a permit or to get a utility to come and move something out of the way, those delays are costly: People are being paid by the hour, equipment is being rented, and roads are torn up while no progress is being made.

A second lesson is that embedding a rail project in a good bus network helps make existing corridors more viable as routes. Even if it’s located next to a highway, a rail station that connects to frequent, fare-integrated bus service can still be heavily utilized, as the first few months of REM’s operations show.

Third, the incentive structure for project spending is backwards. To the public, a major cost overrun or delay is a scandal, so infrastructure builders are strongly motivated to set initial budgets as high as possible to minimize that possibility. But once a target is set, the full amount is very likely to be spent. Instead of focusing so much on avoiding overruns, builders need to pay more attention to reining in initial budgets, using other projects around the world as guidance for what is reasonable. And the public should cut agencies slack if they go a little over budget but the final cost is still low in comparison with others.

Finally, tunneling is enormously expensive and avoiding it where feasible is the way to go. Resisting NIMBY objections to elevated trains can save the public a fortune and allow much more transit to be built.

Think of what other North American cities could build if they followed the REM’s lead. Take New York City, which is planning the Interborough Express (IBX) light rail project between Jackson Heights and Bay Ridge. Its budget is currently $5.54 billion for a 14-mile route along a freight rail corridor. At REM prices, that amount would pay for not only the IBX, but also 31 additional miles of rapid transit — say, a long-promised line along Utica Avenue in Brooklyn, an extension of the IBX to the Bronx, a 6 Train extension in the Bronx, and a rail link to LaGuardia Airport. In other words, New York could complete nearly all the subway projects that have been officially proposed over the past several decades.

Construction costs matter. Montreal’s REM helps point a way toward bringing them down.

Jonathan English is a fellow at the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-30/how-montreal-s-new-rapid-transit-line-saved-millions-per-mile