Texte intégral

REM de l’Est will ruin Chinatown’s landscape: critics

Less than two months after Quebec’s culture minister announced heritage protection for Chinatown, the provincial government’s REM de l’Est project is posing a new threat to the historic neighbourhood, advocates say.

Marian Scott • Montreal Gazette

“It’s two separate entities from the government not talking to each other,” said Jonathan Cha, an urbanologist and member of the Chinatown Working Group.

The $10-billion elevated light-rail project will create a massive visual barrier that will cut off Chinatown from its surroundings and block views that Montrealers have enjoyed for more than a century, he said.

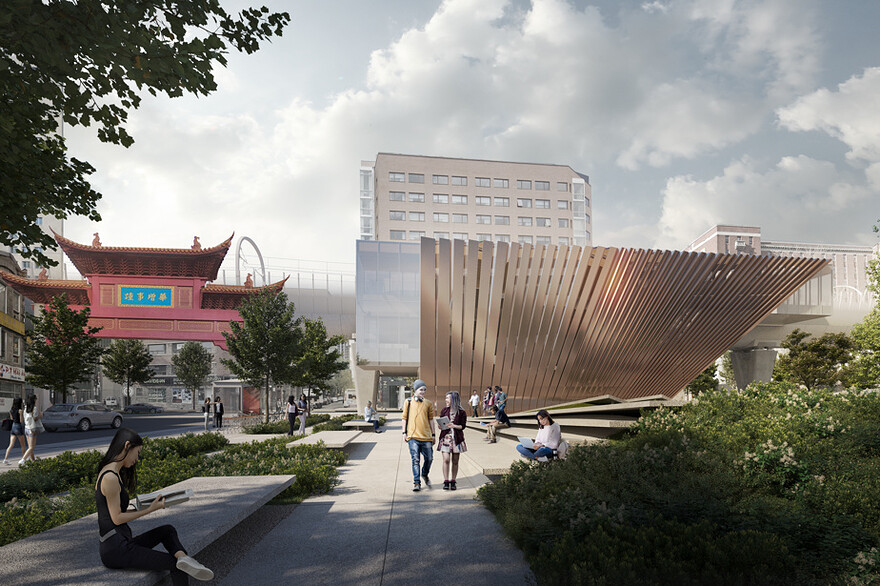

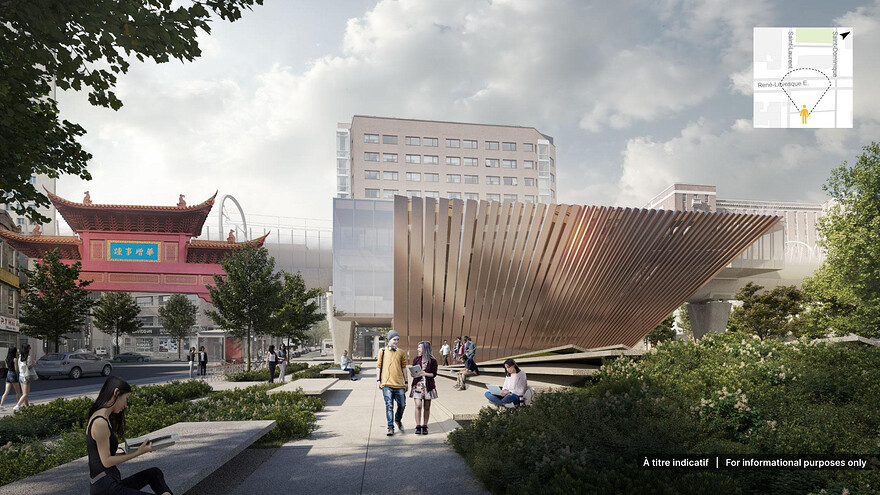

Last week, CDPQ Infra — a subsidiary of the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec in charge of the project — unveiled some design changes it hopes will mollify critics who say the 32-kilometre driverless train network will cause an urban scar comparable to the Metropolitan Expressway.

The tweaks include replacing the utilitarian pillars of the original REM project on the West Island and South Shore with fancier ones and using a lighter colour of concrete.

The REM is also proposing a complete redesign of René-Lévesque Blvd. east of Bleury St. where the elevated train will emerge from an underground tunnel. However, the city of Montreal and Quebec would foot the bill for the improvements, including eliminating four lanes of traffic, adding a bike path and pedestrian walkway, creating an elevated park and lookout and building public squares around the train system’s 32 stations, CDPQ Infra said.

Cha noted the project would turn Jeanne-Mance St. into a dead end at René-Lévesque, preventing pedestrians, cyclists and drivers from circulating between the Quartier des Spectacles and Chinatown.

The elevated railway, topped by a four-metre-high noise barrier, will tower over the neighbourhood, blocking visibility, he said.

“Everything east of St-Laurent Blvd. will be completely blocked by this structure, so anyone coming from the east or from the north will not see the gate of Chinatown anymore,” he said.

“We will lose part of the urban landscape that has been built over the decades and centuries,” Cha added.

Asked about Cha’s comments on Sunday, CDPQ Infra said its engineers and architects “conducted a thorough analysis of existing architectural trends, heritage buildings and infrastructure in 12 communities on the 32-kilometre future network. Each community, particularly the Chinatown and downtown core, will benefit from specific designs.

“We will continue to work with all the stakeholders to make sure the project is perfectly integrated and continue to be optimized, as this new network is particularly important for the east of Montreal.”

But for Cha, the REM de l’Est is just the latest in a long list of government mega-projects since the 1960s that have hemmed in Chinatown on all sides.

“What is sad is that when they created the Ville-Marie Expressway, when they built the Guy Favreau Complex and Palais des Congrès, and when they enlarged René-Lévesque Blvd. (formerly Dorchester), all these major infrastructure projects really isolated Chinatown and this will just add to the barriers,” he said.

Cha also criticized the lack of public consultation on the project, especially considering that the city of Montreal and Quebec’s culture ministry have been working with community organizations in Chinatown for more than two years to chart a future for the district, hard hit by the pandemic and threatened by real-estate development.

“It seems that there’s no dialogue, and that there’s no understanding of the whole process that was done over the past two or three years between the community and the city of Montreal and the Ministry of Culture,” he said.

In January, Culture and Communications Minister Nathalie Roy announced that two historic buildings, as well as the block bounded by de la Gauchetière, St-Urbain and Côté Sts. and Viger Ave., would be classified as provincial heritage sites, meaning they cannot be demolished or altered without her authorization.

Mayor Valérie Plante has enacted zoning limits and municipal heritage status for all of Chinatown.

“When the community and even the city of Montreal are not involved in the design or in the implementation of structures that change not only the landscape, but also the identity of the area in the city, in 2022, this makes absolutely no sense,” Cha said.

Community organizations in Chinatown are asking that the underground portion of the rail line continue east of Bleury. CDPQ Infra has only agreed to bury the portion between Robert-Bourassa Blvd. and Bleury.

The top-down way the REM de l’Est has been managed so far raises fundamental questions about the entire project, Cha said.

Before committing to a major transportation project, decision-makers should hold consultations, involve all levels of government, including the city and transit agencies, confer with experts in the field, and ask the right questions, he said.

“Is this the right thing to do? Are we connecting the right areas of the city? Does this really help the citizens? Does this really contribute to decreasing the number of cars in the city?” he said.

“Public consultation, understanding the different needs and including them in the design of a project” are essential, he said.

Plante has said she wants the city to have a seat at the table, to help planners better integrate the REM de l’Est into the urban landscape.

Given its huge price tag, it could be decades before Montreal sees another major transit initiative, so it’s important to get it right, Cha said.

“I think as a society, we need to ask for more excellence,” he said.

“Everyone who lives in Montreal will see the REM every day,” he added.

mscott@postmedia.com

)

)