Dans The Atlantic

Cities Really Can Be Both Denser and Greener

A classic urban trade-off might not be our destiny. That’s great news for the climate.

By Emma Marris

January 12, 2023, 4:09 PM ET

Jan Richard Heinicke / laif / Redux

When I moved from small-town Oregon to Paris’s 11th arrondissement last summer, the city seemed like a poem in gray: cobblestones, seven-story buildings, the steely waters of the Seine. But soon I started noticing the green woven in with the gray. Some of it was almost hidden, tucked inside the city’s large blocks, behind the apartment buildings lining the streets. I even discovered a sizable public park right across the street from my building, with big trees, Ping-Pong tables, citizen-tended gardens, and “wild” areas of vegetation dedicated to urban biodiversity. To enter it, you have to go through the gate of a private apartment building. Very Parisian.

Dense cities like Paris are busy and buzzy, a mille-feuille of human experience. They’re also good for the climate. Shorter travel distances and public transit reduce car usage, while dense multifamily residential architecture takes less energy to heat and cool. But when it comes to adapting to climate change, suddenly everyone wants green space and shade trees, which can cool and clean the air—the classic urban trade-off between density and green space.

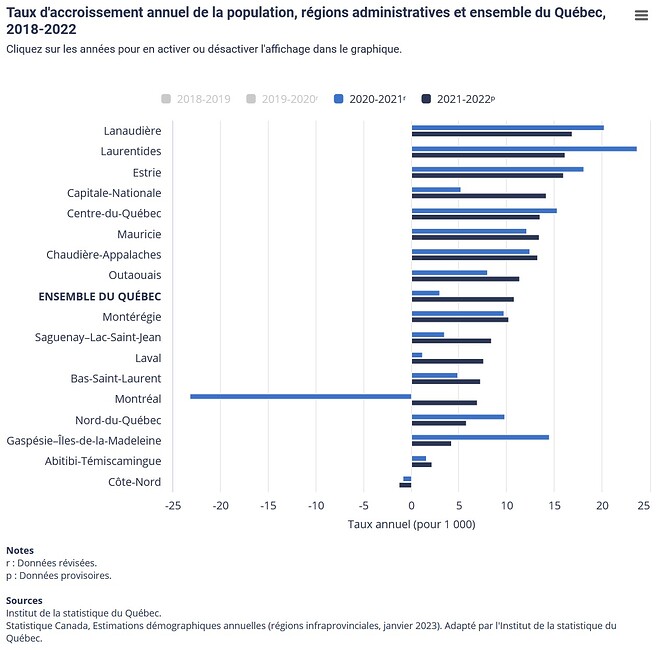

Or, you know, maybe there’s no big trade-off at all. A new analysis of cities around the world published today in the journal People and Nature found only a weak relationship between population density and urban greenery. The team of scientists, led by Rob McDonald, an urban ecologist at the Nature Conservancy, compared satellite images with population-density data in 629 cities across the world. Globally, denser cities had less open space overall than if everyone had private yards, but the amount of public open space was basically unrelated to density and had more to do with history, policy, and culture. One calculation, using data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development for cities outside the U.S., found that a 10 percent increase in density was associated with a 2.9 percent decline in tree cover. Overall, there was a lot of variability, and there were a lot of outliers: Some cities and neighborhoods have both high density and lots of trees or open space. “Density is not destiny,” McDonald told me.

Broadly speaking, the researchers found two ways to avoid the trade-off between density and green space. Take Singapore, one of the densest countries in the world. There, plants are installed on roofs and facades, turning the familiar gray landscape of skyscrapers and overpasses into a living matrix. By law, developers must replace any natural area that they develop with green space somewhere on the building. Meanwhile, in Curitiba, the largest city in southern Brazil, which has tripled in population since 1970, dense housing is built around dedicated bus lanes and interwoven with large public parks and conservation areas. Curitiba also uses planted areas to help direct and soak up stormwater, buffering residential areas from floods. In Singapore, nature shares space with the built environment, while Curitiba packs people in tightly and then spares land for other species inside the boundaries of the city.

With approaches like these, it seems likely that cities could become significantly greener even as they grow denser over time. We can have our energy-efficient metropolises and our cool, clean air smelling of flowers, too. And we’ll really need them both: Cities already tend to run warmer than other places, a phenomenon that will magnify the effects of climate change unless we find ways to lower the temperature. That doesn’t mean that building dense, green cities will necessarily be cheap or easy. Much of the next century’s increased density is likely to come in Africa and Asia, where city budgets tend to be smaller and where some cities are burdened by the legacies of decades of unplanned growth. In the global North, the rise of remote work is flinging many workers toward the suburbs and exurbs, which is a less climate-friendly way of living for as long as we drive around them in gas-powered cars. But even in Europe and North America, the right policies and incentives could counteract that trend—one amenity that tends to lure people to dense urban cores is green space.

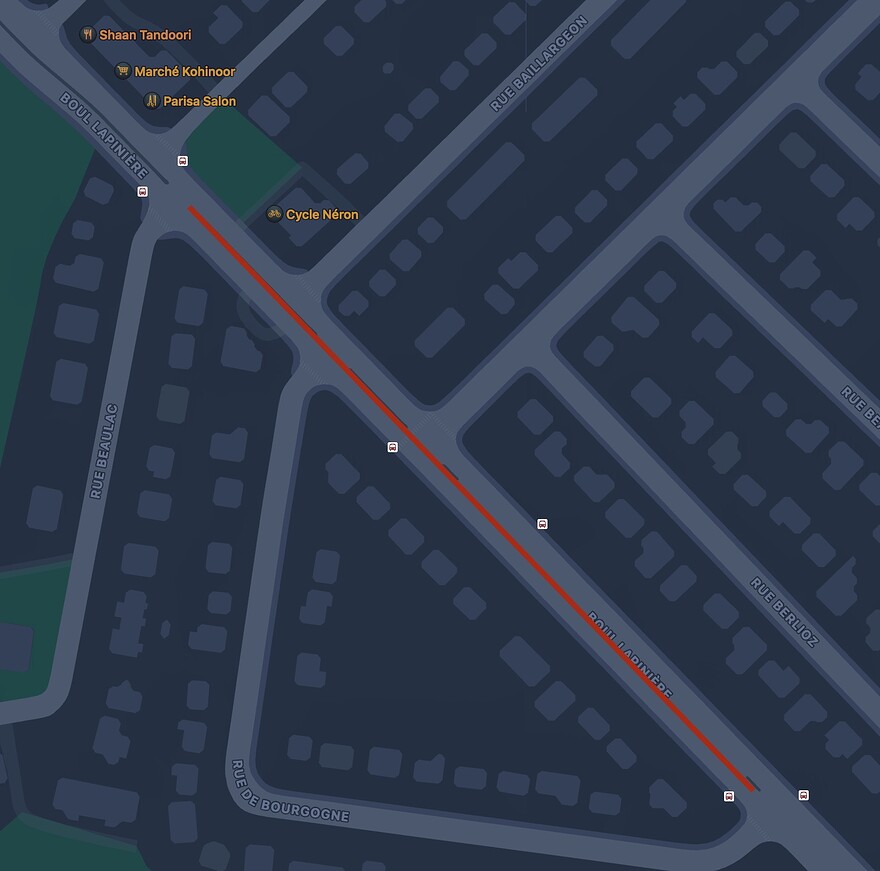

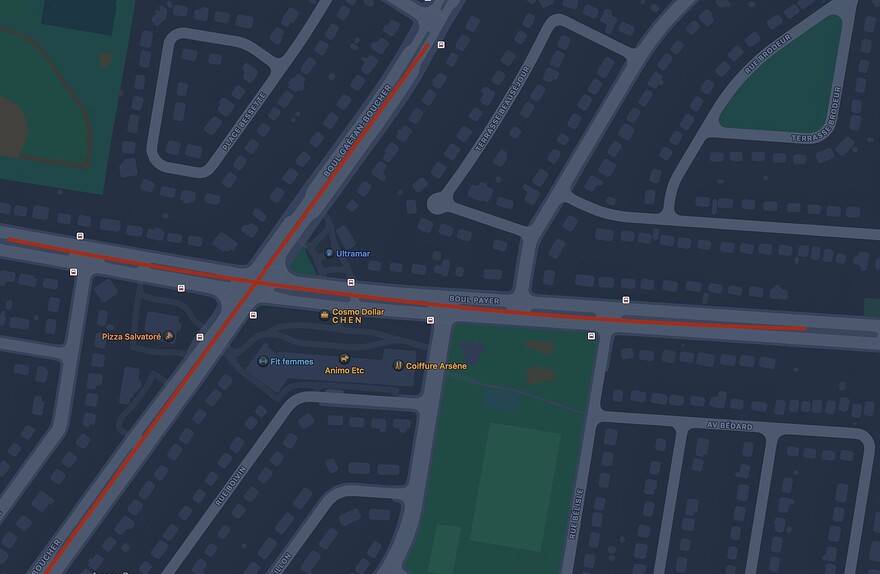

The researchers produced a list of “green interventions” that they recommend, including adding green space along rivers, streams, roads, and rail lines; using planted areas as part of stormwater management; greening vacant lots (even if they will be vacant for only a few years); creating green roofs; and planting more trees along streets. Many cities are already pursuing these sorts of tweaks. In New York City, one of the densest areas of the United States, a coalition of advocacy groups called Forest for All NYC is pushing for the city to increase its tree cover from 22 percent to 30 percent by 2035—especially in areas with low-income households and high proportions of people of color. Emily Nobel Maxwell, the director of the Nature Conservancy’s Cities Program in New York, told me that the potential of green roofs in the city has barely been tapped. At the moment, there are about 730 green roofs in the city, but that’s less than 0.1 percent of the available rooftop real estate. “This is three-dimensional, and all of our surfaces matter,” Maxwell said.

Still, not everyone is so sure that the density/green space trade-off is mostly a myth. Shlomo Angel, an expert on urban density at New York University who wasn’t involved in the study, told me that his own research using different methods shows a stronger trade-off than this new study does. But he agrees that there are ways around the trade-off, including one that he says was not emphasized enough in the study: building high. By stacking urban residents one atop the other, land is spared for parks, trees, and gardens. That, he says, is Singapore’s real secret, not its green roofs. “In order to have more open space, you have to make it possible to build higher,” Angel said. “That’s the main way of removing that conflict.”

Paris is aesthetically committed to a lower profile, but strict height limits were relaxed in the outer arrondissements in 2010. The more I explore Paris, the more green spaces I find. The Haussmann-style apartment buildings that the city is known for come with delicate wrought-iron balconies, which many residents cram with a huge array of plants, whether geraniums or banana trees. Green roofs and facades are common. As of this year, new buildings in France larger than 500 square meters will have to dedicate 30 percent of their roof space to solar panels or plants. Public parks, including two large forested areas on either end of the city, provide a shared refuge from the gray. And street trees line many of the larger streets.

Just up the block from my apartment building, there’s a London Plane tree that was planted in 1880 that’s 75 feet tall. Its trunk is more than 13 feet in circumference. I know these stats because they are proudly listed (in metric equivalents, naturally) on a sign affixed to the tree. But Paris wasn’t always able to brag about its urban forest. “In Paris in the 1600s, there were no street trees and no publicly accessible parks,” McDonald said. They emerged after the French Revolution as private gardens were made public. Trees were planted along Paris’s boulevards starting in the 1800s. “We reinvented cities once,” he said. “We can do that again.”