Texte complet : How a Cold, Hilly Canadian City Became a Year-Round Cycling Success Story

How a Cold, Hilly Canadian City Became a Year-Round Cycling Success Story

The average daily temperature in February is 26 degrees Fahrenheit, with overnight lows at 12 degrees. There are 12 days of precipitation (primarily snow). There’s a massive, 764-foot-high hill (locals call it a Mont) smack dab in the middle of the city. Who would go cycling in such conditions? Montrealers, and the city’s bikeshare program has the stats to prove it.

Montreal’s bikeshare program, called BIXI, has grown exponentially since launching in 2009. With over 10,000 bikes, it has the largest fleet in Canada and one of the largest in North America. BIXI has a user base of more than 500,000 riders, who took almost 12 million trips in 2023, more than double the 5.8 million in (pre-COVID) 2019. This demand led BIXI to add winter service for the first time this season.

Opponents of investing in human-powered infrastructure often point to some impediment that makes their city less amenable to cycling than, say, sunny San Diego. 70,274 bike rides in February in one of the coldest and hilliest cities in North America suggests they may be underestimating that demand.

Pierre-Luc Marier, BIXI’s communications director, attributes its impressive growth to a wide range of factors. On the product side, it was important to launch with high-quality cycles, a well-designed network, and a pricing structure that riders are comfortable with.

Decisions made on the planning side, and cooperation from the city and other stakeholders also set BIXI, and Montreal cycling in general, on a solid path. BIXI took a holistic look at how it would fit within the broader transportation framework of the city, says Marier. “Integration with public transit is key. Planning along infrastructure is very important.”

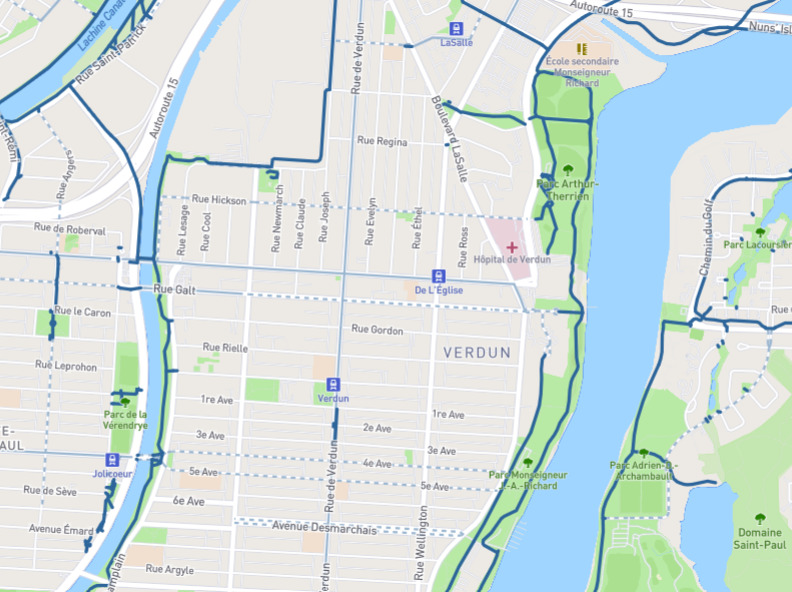

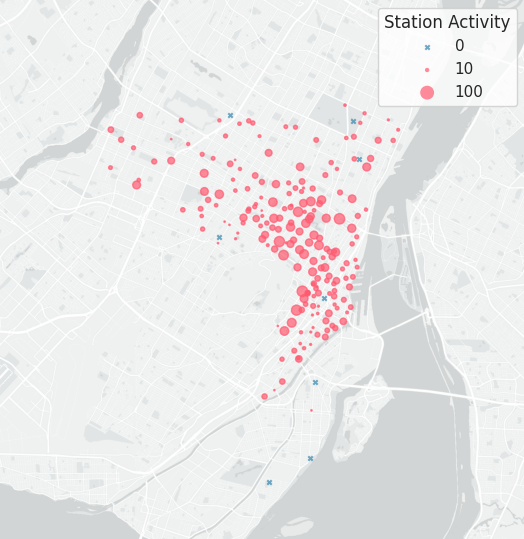

But most important of all is making the network available where users live and travel between. The city of Montreal is just one population center in the metropolitan area, so BIXI created 865 stations including the surrounding municipalities of Westmount, Mount Royal, East Montreal, Longueuil, Boucherville, Terrebonne, and Laval. Using dedicated docking stations eliminates the complaints many bike (and in particular, scooter) vendors have faced for cluttering up cities.

BIXI’s fleet now includes 2,600 e-bikes, and Marier says they’ve been key to expanding service. Mont Royal looms over downtown at an elevation of 764 feet, and is the site of multiple universities, including a campus of Universite de Montréal. Despite being a popular area for rides overall, very few riders made it all the way up the hill until BIXI added e-bikes in 2019. Then the university offered BIXI subscriptions to its employees, and now BIXI finds that 75% of the bikes at those stations are electric-assist.

Marier sees two important elements contributing to this success, the institutional support that encourages more workers to ride, and the fact that a combination of good biking infrastructure and the right type of bike enabled “a new behavior. Because they can go to their meetings and they feel fresh, they don’t feel sweaty at all.”

He says that BIXI is focused on using user data to analyze and improve its routes. “You have thousands of Point A to Point B [trips] every day. So you need to understand it,” says Marier, adding that BIXI shares all data with the city planner’s office, and has benefitted from a collaborative relationship with Montreal area transportation officials, who’ve shown strong commitment to increasing multimodal options.

Author Daniel Piatkowski has studied cities that have effectively embraced cycling for his upcoming book, Bicycle City: Riding the Bike Boom to a Brighter Future. He found that one key factor has been “bringing bicycling into the fold of the larger system.” He cites an example in Minneapolis in which a federal grant funded a bike planner position in the city government, which changed cycling “from being this thing that’s advocate-driven to this thing that is driven from within.”

Piatkowski points out that the city most revered for being bicycle friendly wasn’t always that way. “People talk about Amsterdam in this sort of mythical way, as if the Dutch are born on bicycles.” But like much of Europe and North America, the Netherlands committed heavily to the car in the 20th century. The shock of the 1970s energy crisis led the country to lessen its dependence on foreign oil and to seek more economical transportation options. That, plus the work of highly effective cycling advocates, helped lead to a retooling of urban infrastructure that turned “pretty much all of the Netherlands into a really bicycle-friendly place that’s now leading the world.”

Piatkowski adds that effective cycling policy has broad benefits for a city. “Cycling success stories also really have to have all the other pieces, like walking and public transport … And as you make one better, it makes the other ones better too. So investments in each other always add up.”

While Marier is excited about the success of BIXI’s business, he points to a broader victory that benefits everyone in Montreal. BIXI offers “more than a bikeshare system; it’s easy public transportation,” accounting for as many trips as a bus network. And with 25% of all Montrealers using BIXI in 2023, “bicycling as a transportation solution is rapidly increasing.”