Article d’ “opinion”, diffusé dans… le Toronto Star !?

Montreal’s controversial REM train east is a product of Quebec’s top-down political culture

Toronto Star | By Alexander Hackett, Contributor | Tue., Oct. 12, 2021timer 3 min. read

The Montreal REM project has the making of another classic boondoggle. J.F. SAVARIA PHOTO

For Montrealers old enough to remember the ’60s and ’70s, the prospect of yet another massive infrastructure project of questionable value and dubious execution will come as something of a déjà vu.

The REM de l’Est (or Réseau Express Métropolitain), announced by the Legault government and Quebec’s pension fund last December, has all the makings of a classic boondoggle.

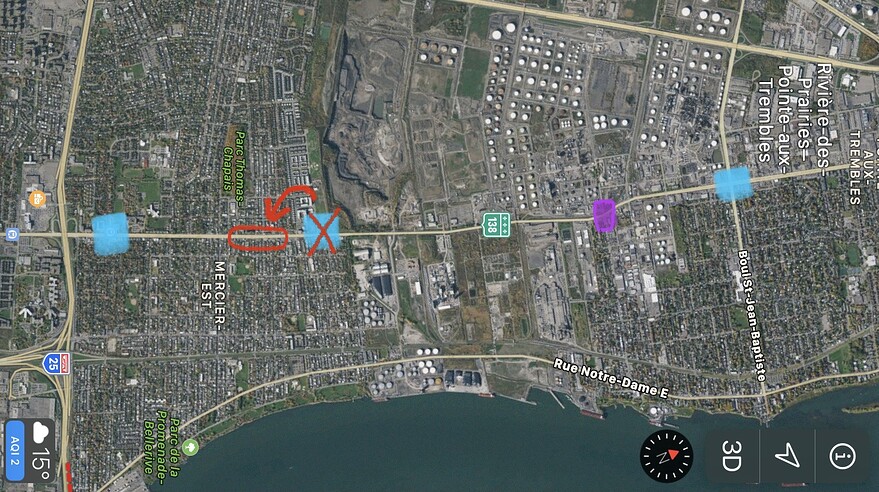

The proposed electric train would roll through the city’s downtown core on a series of raised pylons, linking historically underserved east end neighbourhoods with Central Station at a cost of $10 billion. Twenty-three stations are planned over 32 kms, and it will join western portions of the REM already under construction (and over budget).

While everyone agrees on the need for more public transit, the rushed, take-it-or-leave-it way in which developer CDPQ Infra has rammed the project through has shocked many citizens.

“The special law that created CDPQ Infra in 2015 gave them extraordinary powers,” says Gérard Beaudet, professor of urban planning at the Université de Montréal. “It put them above all the normal consultation procedures for the development of public transit in the Greater Montreal area.”

Questions of esthetic design, the necessity of building above ground and possible alternative routes have all been suppressed by the “political and financial authoritarianism” of the project, he says.

“Instead of responding to the needs of the population, this is about profit. There has been a complete lack of transparency on their behalf, and so we can’t even know why they’re making these decisions.”

Where to begin?

You could start with the fact the government’s awarding of a for-profit, no-bid contract to a branch of its own pension fund looks suspiciously like someone paying their right hand with their left.

Subcontracts go to the usual suspects, including SNC-Lavalin, who were until very recently banned from bidding on World Bank projects due to their own dodgy track record.

CDPQ Infra initially stated that tunnelling beneath the downtown core would be impossible, and could possibly result in the collapse of some skyscrapers. But they didn’t provide any studies to back up these claims, which have since been contested by independent engineers.

After a public outcry, they changed their tune and agreed to build a 500 metre tunnel near the end of the train’s route, thus sparing a central part of downtown from disfigurement. This casual change of tack created a glaring credibility gap for the company.

In Vancouver, by comparison, a proposal to prolong the SkyTrain into the downtown studied some 200 scenarios over many years. The aerial option was overwhelmingly rejected, as officials said it would be disastrous in such a densely populated area.

Total number of CDPQ Infra studies: Two.

In February, two Montreal architecture firms quit the project, saying it was so ugly and problematic they didn’t want to be associated with it.

“CDPQ is making it all up as they go along,” says Beaudet. “There’s no proof that we actually need this train, and no coordination with existing lines in the suburbs. It will render many of those obsolete.”

In a city still healing from such poorly constructed, space-age white elephants as the Turcot interchange, the first Champlain bridge (retired after 57 years), and the Ville-Marie expressway — which razed large swathes of historic buildings — locals are understandably skeptical about the wisdom of erecting another concrete behemoth downtown.

No list of Montreal construction follies would be complete without mentioning the Olympic Stadium and more recently, the LSD-inspired ziggurat that is the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) — the biggest construction fraud in Canada’s history.

What these projects have in common are the provincial and municipal politicians who put them in motion and let them spin out of control — the likes of bullish ’60s mayor Jean Drapeau, Maurice Duplessis and now François Legault.

It’s big man style of top-down governance that brooks no dissent, doesn’t like consultations, and places the ends above the means.

And it’s especially disheartening when considering that the trend in most major cities — from New York to Sydney and Toronto — is toward a recuperation of urban space for green or public purposes.

Construction on the REM de l’Est is slated to begin in 2023.

Prochaine station: Pierre-Bernard.

Prochaine station: Pierre-Bernard.

1. Défis de recrutement

1. Défis de recrutement 2. Impacts sur l’environnement

2. Impacts sur l’environnement 3. Pression sur les infrastructures et les municipalités

3. Pression sur les infrastructures et les municipalités